ZK Regex is a powerful tool to be able to general string parsing with ZK. We use it as the primary way to parse data out of emails to prove on-chain.

Table of Contents

- High-level Overview of zk-regex

- Regex Example

- Using zk-regex

- Synthesizing Circom Circuits for Regex

- 2024 Expansion and Explanation

- Halo2 ZK Regex

- Reef

High-level Overview of zk-regex

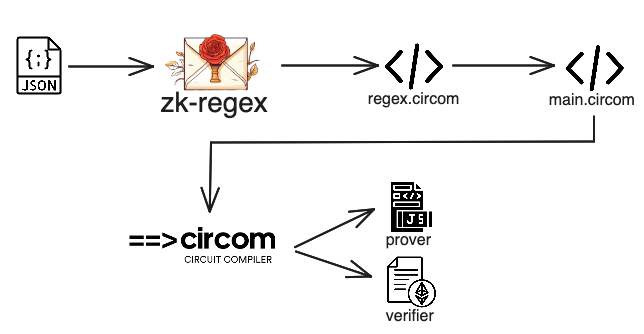

The figure below describes the high-level interactions for using zk-regex. First, we define a regex for which we want to create a proof, then we use zk-regex to create the respective Circom code. In another Circom template, we can use our regex template as a component to feed data and get an output that represents whether the input satisfies the regex. Note that we can also produce a reveal array in the regex template to process a particular part of the input string that matches a specific regex. Afterward, we can use the circuit like any Circom circuit (e.g., perform preprocessing and create a JavaScript prover and a Solidity verifier). This allows us to perform regex checks on-chain using off-chain computations, without revealing the input string or only revealing part of it.

Our latest update (May 2024) allows one to use a much wider set of regex syntax and supports all international UTF-8 characters, and uses a new method of regex generation via merging DFAs in order to do so. It has been audited by ZK Security, and the audited release is labeled 2.1.0 on Github.

zk-regex overview.

Consider the following regex example:

m[01]+-[ab]+;

To use zk-regex to obtain a Circom circuit that creates and verifies a proof for inputs that match this regex, we can use the following JSON:

{

"parts": [

{

"regex_def": "m[01]+-[ab]+;",

"is_public": false

}

]

}

To produce the Circom circuit, we run the following command:

zk-regex decomposed -d ./simple_regex_decomposed.json -c ./simple_regex.circom -t SimpleRegex -g true

This results in a Circom template with the following structure. Note that we must define the number of bytes our input message should be at compile time. This limits how large the message can be.

template SimpleRegex(msg_bytes) {

signal input msg[msg_bytes];

signal output out;

...

}

To call that template as a component in another template, we could use the following code:

signal simpleRegexMatch <== SimpleRegex(maxLength)(msg);

simpleRegexMatch === 1;

This will result in accepting the proof if the msg matches the regex; otherwise, the constraint simpleRegexMatch === 1 will fail.

Now let's consider the case where we want to reveal the part between - and ;. In this case, we would use the following JSON:

{

"parts": [

{

"regex_def": "m[01]+-",

"is_public": false

},

{

"regex_def": "[ab]+",

"is_public": true

},

{

"regex_def": ";",

"is_public": false

}

]

}

This will result in a Circom template with the following structure:

template SimpleRegex(msg_bytes) {

signal input msg[msg_bytes];

signal output out;

...

signal output reveal0;

...

}

That can be used as follows:

signal (simpleRegexMatch, simpleReveal[maxLength]) <== SimpleRegex(maxLength)(msg);

simpleRegexMatch === 1;

The reveal part is an array that is full of zeros, and in the positions of the revealing part, it contains the input that matches that part of the regex. For example, for the input m01-aab; and length of the message set to 10, the result of the reveal part would be aab. Note that in practice the template takes as input UTF-8 encoded messages in decimal format. Hence, the actual input array would be ["109", "48", "49", "45", "97", "97", "98", "59", "0", "0"] (you can use this tool for the conversion), and the reveal array would be ["0", "0", "0", "0", "97", "97", "98", "0", "0", "0"].

Synthesizing Circom Circuits for Regex

zk-regex operates on top of Deterministic Finite Automatons (DFAs), proving that a string satisfies a DFA and optionally revealing parts of the transition steps involved.

Regex to DFA

To understand how that works, we should go a step backward. First of all, a Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) is a finite-state machine that accepts or rejects a given string of symbols by running through a state sequence uniquely determined by the string. A regular expression can be converted to a DFA using the following process:

- Parse the Regular Expression: Initially, the regex string is parsed into a data structure, such as a parse tree or an abstract syntax tree (AST). This structure represents the hierarchical organization of the regex, including its characters, operators, and sub-expressions.

- Convert the Parse Tree to an NFA: Using the parse tree, a Non-deterministic Finite Automaton (NFA) is constructed. An NFA is a finite-state machine that may include several possible transitions for a single state and a given input symbol.

- Convert the NFA to a DFA: The NFA is then transformed into a DFA, which ensures a single, deterministic transition for each state and input symbol combination. This process can also include minimizing the DFA to reduce its complexity without changing the language it recognizes.

These steps are foundational in compiling regex into a format that can be processed efficiently. More information on this process can be found in various online resources.

DFA Definition

A deterministic finite automaton is defined as a 5-tuple, (, , , , ), where:

- is a finite set of states,

- is a finite set of input symbols (the alphabet),

- is the transition function ,

- is the initial state, and

- is the set of accept states, .

Example DFA Transition Matrix

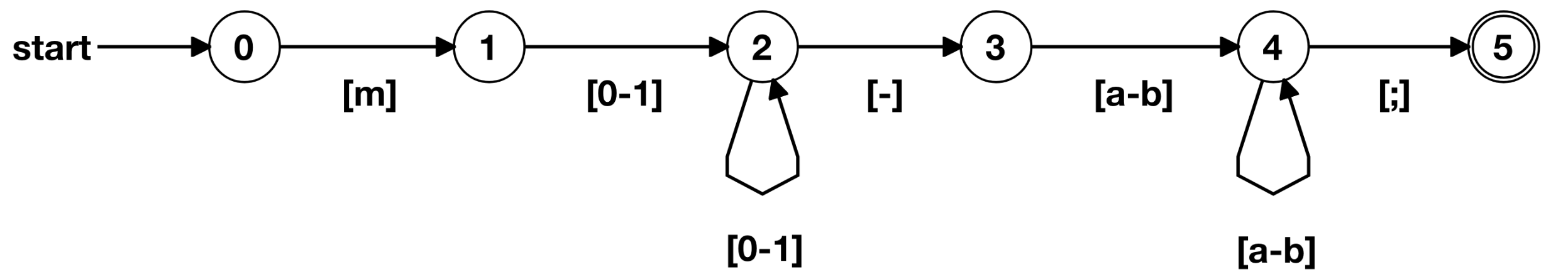

Furthermore, typically, we have a transitions matrix for a DFA. Let's consider our example from above, i.e., m[01]+-[ab]+;.

DFA of m[01]+-[ab]+; (produced using https://zkregex.com/min_dfa).

The transition matrix will be:

| DFA State | Type | m | [0-1] | - | [a-b] | ; |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | |||||

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 2 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 3 | 4 | |||||

| 4 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| 5 | Accept |

For a string (or part of the input string) to match the regex, it must match the DFA, or part of it should satisfy it.

Synthesizing Circom Code and Applying Constraints

Now, we can proceed to explain how zk-regex goes from the decomposed JSON input to the circom circuit and how it works. Initially, we will use an example where we have a single part and don't reveal anything. After that, we will see what happens when we have multiple parts and how we reveal some parts of the matched string.

The first step in the compiler, once all the inputs are read and parsed, is to convert the regex to a DFA. This is done using DFAGraphInfo::regex_and_dfa. If we have multiple regexes, their DFAs are computed separately and merged. Then, we compute which substrings should be revealed. The result is a structure called RegexAndDFA, which contains regex_str, dfa_val, substrs_defs. Let's first understand what happens when we have a single regex.

Let's consider the case where we have the following input.

{

"parts": [

{

"regex_def": "m[01]+-[ab]+;",

"is_public": false

}

]

}

The resulting RegexAndDFA will be:

RegexAndDFA { regex_str: "m[01]+-[ab];", dfa_val: DFAGraph { states: [DFAState { type: "", state: 0, edges: {1: {109}} }, DFAState { type: "", state: 1, edges: {2: {48, 49}} }, DFAState { type: "", state: 2, edges: {2: {48, 49}, 3: {45}} }, DFAState { type: "", state: 3, edges: {4: {97, 98}} }, DFAState { type: "", state: 4, edges: {5: {59}} }, DFAState { type: "accept", state: 5, edges: {} }] }, substrs_defs: SubstrsDefs { substr_defs_array: [], substr_endpoints_array: None } }

It transforms it by using the rust DFA:Builder after wrapping the regex into another regex with a specific anchored start ^ and end $, i.e.,^Input_Regex$.

The output of the DFA: Builder is the following:

D 000000:

Q 000001:

*000002:

000003: m => 8

000004: - => 5, 0-1 => 4

000005: a-b => 6

000006: ; => 7

000007: EOI => 2

000008: 0-1 => 4

This is transformed into a graph, and it is sorted. Note that *000002 is the accepting state, and EOI is the end of the input. The parsing and conversion are happening in the function parse_dfa_output. Then, the graph is post-processed by dfa_to_graph to get the decimal representation of the UTF-8 characters, which is the alphabet of the provided regex. This function does the following:

- Define a custom key mapping for

"\\n", "\\r", "\\t", "\\v", "\\f", "\\0"to their UTF-8-encoded decimals. - It specially handles the space (

- It handles ranges (e.g.,

0-9), by generating a set of all UTF-8 encoded values within that range. - It also specially handles the custom key mappings

- Finally, it also specially handles hexadecimal representations (

\xNN); it parses the string after\xas a hexadecimal number. Note thatDFA:Buildertranslates non-ASCII characters to their hexadecimal UTF-8 encodings.

After having the RegexAndDFA, then it uses the RegexAndDFA:gen_circom to generate the Circom circuit, which in turn uses the gen_circom_allstr function to produce the Circom code for the DFA.

The gen_circom_allstr is a complicated function, and we believe it should be further documented and decoupled while also being extensively tested to reveal any subtle bugs. In a nutshell, it works as follows.

fn gen_circom_allstr(dfa_graph: &DFAGraph, template_name: &str, regex_str: &str) -> String

dfa_graph — a collection of states and, for each state, transitions to other states labeled by letters.

template_name — the name of the generated Circom template.

regex_str — the regex string implemented by the generated Circom template.

Important variables:

n: usize— number of states in the DFA.mut rev_graph: BTreeMap<usize, BTreeMap<usize, Vec<u8>>>— reverse graph of the DFA, where the key is the state index and the value is a map of the states, that have transitions to the key state, and the letters of the transitions.accept_node: usize— the index of the accepting state of the DFA.mut lines: Vec<String>— the core generated Circom template code, each line in a separate element.mut declarations: Vec<String>— the initial declarations in the Circom code: pragma, import, template declaration, input and output signals, components defined at the top of the template.mut init_code: Vec<String>— the initialization code forstates[0][0..n-1].mut accept_lines: Vec<String>— the code for the computing the output from the accepting state.

High level flow:

- Populate the reverse graph and

to_init_graphbased on the DFA. Also, identify the accepting states. - Check if there is only one accepting state, if not, panic.

- Initialize counters for different types of checks.

- Initialize data structures for different types of checks.

- Generate the Circom code for each state in the DFA.

- Generate the Circom code for the final state.

- Combine all the generated Circom code and return.

The main signals and components used to determine if we have a match are:

signal in[num_bytes];: This signal represents the user input prepended by256.states[num_bytes+1][n];: This signal represents the transitions of states based on the input. Every time we go from a valid state to an invalid one, we transition back to the initial state.states_tmp[num_bytes+1][n];: This is a helper signal to handle complicated conditions.from_zero_enabled[num_bytes+1];: This signal checks if we are at the zero state.state_changed[num_bytes];: This signal tracks the steps we took to change the state successfully (i.e., progress). The comparison components used to check if an input matches a character, a set of characters, or a range. These components are:IsEqual,LessEqThan,MultiOR, etc.final_state_result: This component is used to constrainoutto1if we reach the acceptance state at some point.is_consecutive[msg_bytes+1][n-1];: Keeps track of whether the matches are consecutive across the input, ensuring that patterns requiring consecutive elements (like a*) are correctly validated.

The steps in the Circom circuit are:

- It has a main loop that goes over the inputs and mainly sets and constrains

statesandstate_changed. - It sets and constrains

final_state_result, which sets and constrainsout. - It computes and appropriately constrains the

is_consecutivesignal.

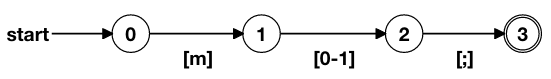

For simplicity, we are going to describe how that works for the regex m[ab]; and the input:

["109", "0", "109", "98", "59"]

So, our DFA is the following.

Visualisation for DFA of m[ab]+; (produced using https://zkregex.com/min_dfa).

The initialization Circom code would be:

signal input msg[msg_bytes];

signal output out;

var num_bytes = msg_bytes+1;

signal in[num_bytes];

in[0]<==255;

for (var i = 0; i < msg_bytes; i++) {

in[i+1] <== msg[i];

}

component eq[4][num_bytes];

component and[3][num_bytes];

component multi_or[1][num_bytes];

signal states[num_bytes+1][4];

signal states_tmp[num_bytes+1][4];

signal from_zero_enabled[num_bytes+1];

from_zero_enabled[num_bytes] <== 0;

component state_changed[num_bytes];

for (var i = 1; i < 4; i++) {

states[0][i] <== 0;

}

Note that the in has one more initial byte that is set to the invalid decimal 255. states is two-dimensional. The first dimension is set to num_bytes+1 because we want to have a dummy initial array in the beginning to process the initial byte, and it is used to keep the state for each byte. The second dimension represents the states of the DFA. The other components are used to make comparisons and evaluations.

Next, we have the main loop, which is implemented as follows.

for (var i = 0; i < num_bytes; i++) {

state_changed[i] = MultiOR(3);

states[i][0] <== 1;

eq[0][i] = IsEqual();

eq[0][i].in[0] <== in[i];

eq[0][i].in[1] <== 109;

and[0][i] = AND();

and[0][i].a <== states[i][0];

and[0][i].b <== eq[0][i].out;

states_tmp[i+1][1] <== 0;

eq[1][i] = IsEqual();

eq[1][i].in[0] <== in[i];

eq[1][i].in[1] <== 97;

eq[2][i] = IsEqual();

eq[2][i].in[0] <== in[i];

eq[2][i].in[1] <== 98;

and[1][i] = AND();

and[1][i].a <== states[i][1];

multi_or[0][i] = MultiOR(2);

multi_or[0][i].in[0] <== eq[1][i].out;

multi_or[0][i].in[1] <== eq[2][i].out;

and[1][i].b <== multi_or[0][i].out;

states[i+1][2] <== and[1][i].out;

eq[3][i] = IsEqual();

eq[3][i].in[0] <== in[i];

eq[3][i].in[1] <== 59;

and[2][i] = AND();

and[2][i].a <== states[i][2];

and[2][i].b <== eq[3][i].out;

states[i+1][3] <== and[2][i].out;

from_zero_enabled[i] <== MultiNOR(3)([states_tmp[i+1][1], states[i+1][2], states[i+1][3]]);

states[i+1][1] <== MultiOR(2)([states_tmp[i+1][1], from_zero_enabled[i] * and[0][i].out]);

state_changed[i].in[0] <== states[i+1][1];

state_changed[i].in[1] <== states[i+1][2];

state_changed[i].in[2] <== states[i+1][3];

}

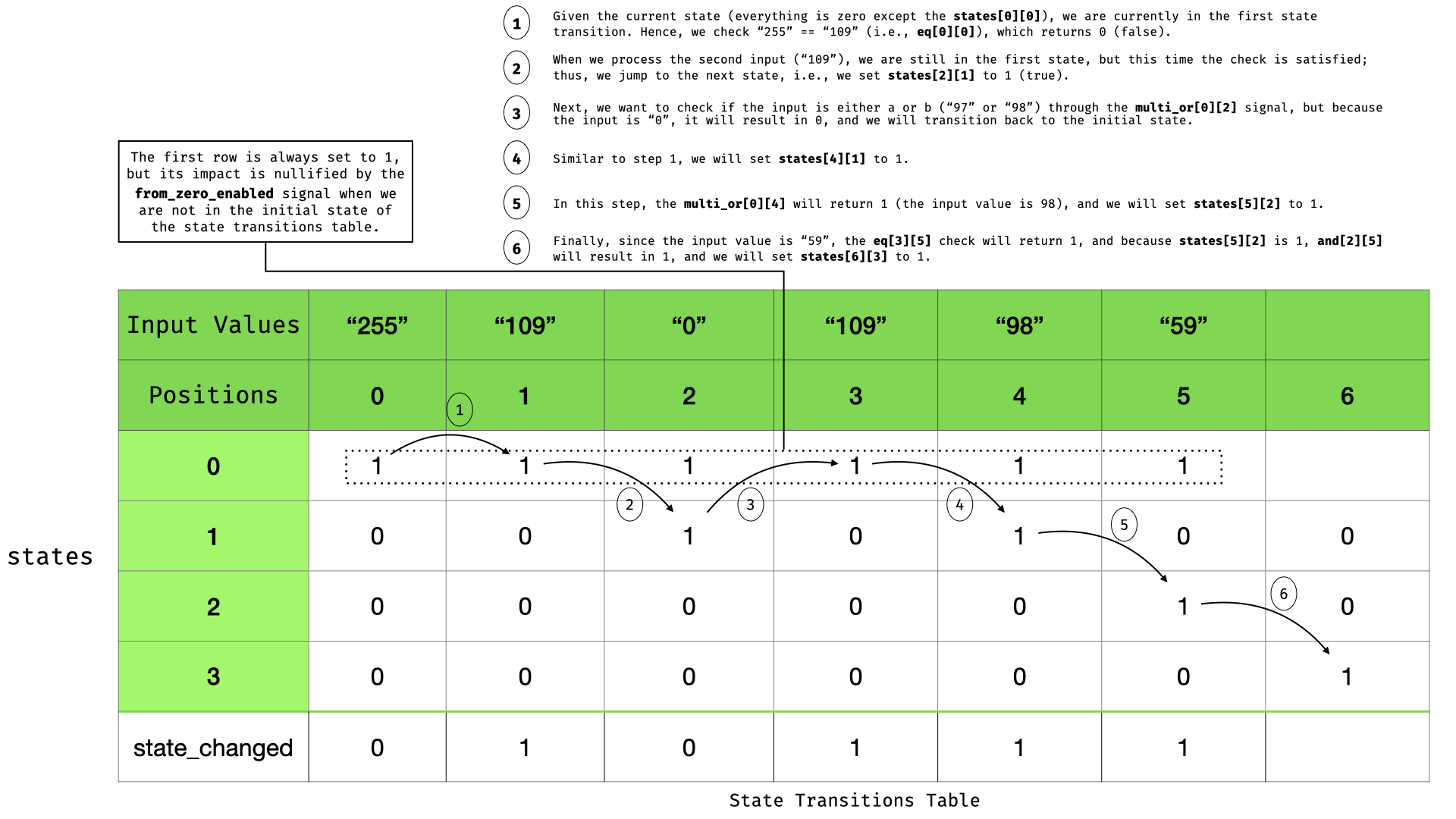

So, let's see how the transition signal states gets filled and how we constrain it to the correct value.

The initial values for states are:

| state | 0 |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 |

Where state column represent the DFA states, and 0 the current state when we processing in[0] (255).

The first byte we process is 255 and the resulting state will be the following. We also keep track of the state_changed (sc) variable. Note, that we set the state from 1 to 3 for the next input.

| state | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 |

| sc | 0 |

We set all three states to 0 because we are not making the correct transition from the first state (0) to state' 1', i.e., transitioning to 109 to go to state 1. Next, we will be in state 0 and need m (109) to transition. Here, we should also note that we always set state 0 to 1, but we handle that later with the from_zero_enabled component in case we are not actually in state 0. Our next input is 109. The resulting table will be:

| state | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| sc | 0 | 1 |

Note that we transition to state 1 because and[0][i] is 1 (meaning that state[i][0] is 1 and current input is 109), and from_zero_enabled is 1.

Next, being in state 1 and processing the next input, we want to check if we can transition to state 2, which means that we need input to be 97 or 98. As it is not (0) we change all the states for the next input to 0 which means we return to state 0. Following the same logic, we eventually will have the following state transition table.

State transitions table.

The following code verifies that we have at least a match:

component final_state_result = MultiOR(num_bytes+1);

for (var i = 0; i <= num_bytes; i++) {

final_state_result.in[i] <== states[i][3];

}

out <== final_state_result.out;

This is because we check if we reach the state 3, which is the accepted state, at least once. The final part of the code is the following:

signal is_consecutive[msg_bytes+1][3];

is_consecutive[msg_bytes][2] <== 1;

for (var i = 0; i < msg_bytes; i++) {

is_consecutive[msg_bytes-1-i][0] <== states[num_bytes-i][3] * (1 - is_consecutive[msg_bytes-i][2]) + is_consecutive[msg_bytes-i][2];

is_consecutive[msg_bytes-1-i][1] <== state_changed[msg_bytes-i].out * is_consecutive[msg_bytes-1-i][0];

is_consecutive[msg_bytes-1-i][2] <== ORAnd()([(1 - from_zero_enabled[msg_bytes-i+1]), states[num_bytes-i][3], is_consecutive[msg_bytes-1-i][1]]);

}

Which is a reverse loop to keep track of the state transitions using consecutive correct transitions.

Merging DFAs

Remember that we can split our regex into multiple parts. This functionality works by parsing each part in a separate DFA and then merging the DFAs by adding an anode from the first's accepted state to the second's first, etc.

Revealing sub-parts

When using the decomposed JSON and select to reveal a part of a regex, the regex_and_dfa code will identify from an accepted state which transitions lead to it and will add it to the substr_defs_array as a set of edges for the DFA of each public regex part. Then, in the Circom code, some additional code will be produced per public substring to be revealed that will be an output signal array of the size of the input message and will be filled with 0's and the input value for the part of the regex it matches. For example, for the following JSON.

{

"parts": [

{

"regex_def": "m",

"is_public": false

},

{

"regex_def": "[ab]",

"is_public": true

},

{

"regex_def": ";",

"is_public": false

}

]

}

The following Circom code will be produced:

// substrings calculated: [{(1, 2)}]

signal is_substr0[msg_bytes];

signal is_reveal0[msg_bytes];

signal output reveal0[msg_bytes];

for (var i = 0; i < msg_bytes; i++) {

// the 0-th substring transitions: [(1, 2)]

is_substr0[i] <== MultiOR(1)([states[i+1][1] * states[i+2][2]]);

is_reveal0[i] <== is_substr0[i] * is_consecutive[i][2];

reveal0[i] <== in[i+1] * is_reveal0[i];

}

That checks if the proper state transitions are enabled and if they are part of a consecutive string. Then, it reveals the input; otherwise, it sets the value to 0. Note that this code has some issues, as demonstrated in finding "In accepting input, reveal array reveals more values than the matching ones". Also, the user should be careful if the 0 value is supposed to be part of the revealed match.

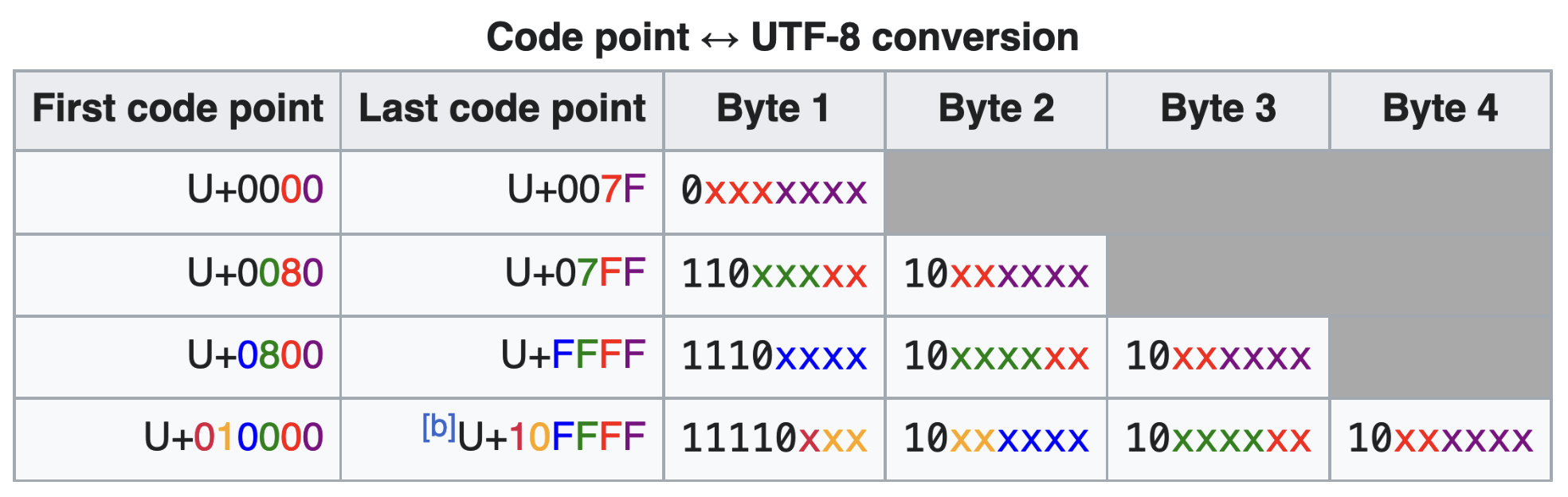

UTF-8 encoding

zk-regex works on any UTF-8 encoded Unicode character in its decimal representation. This means that . should match any valid UTF-8 encoded beyond the line terminator. More specifically, every character that is described using the following format and represented in its decimal form is accepted (note that it should broken into bytes), and a single character could be broken into multiple bytes, resulting in multiple consecutive nodes in the DFA. Still, there needs to be more specific documentation on what is accepted and what is not. It is up to the user to define a verifier by either using a very strict regex that will be sure to accept only the strings that he wants or defining and checking how a message should look.

UTF-8 conversion table (ref: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UTF-8).

2024 Expansion and Explanation

For our audit in May 2024, we greatly expanded the scope of the zk-regex library and rewrote all the Typescript in Rust. The regular expressions supported by our newest compiler have the following limitations:

- Regular expressions where the results differ between greedy and lazy matching (e.g., .+, .+?) are not supported.

- The beginning anchor ^ must either appear at the beginning of the regular expression or be in the format (|^). Additionally, the section containing this ^ must be non-public (is_public: false).

- The end anchor $ must appear at the end of the regular expression.

- Regular expressions that, when converted to DFA (Deterministic Finite Automaton), include transitions to the initial state are not supported (e.g., .*).

- Regular expressions that, when converted to DFA, have multiple accepting states are not supported.

- All UTF-8 characters are supported, including international characters.

This is because of the new way we generate and chain DFAs. Instead of providing a configuration defining how to interpret public and private parts after generating the DFA, we input it before generating the DFA. Then, we split up the regex into seperate DFAs for the public and private parts, and feed all the output states of each stage into the input states of the next stage. We then merge and minimize the resulting DFAs.

Note that zkregex.com still reflects the 1.0 compiler and will be updated in Q3 2024, so there is no longer any DFA visualization (nor manual state selection needed).

Halo2 ZK Regex

We also offer a halo2 zk regex library, that is substantially faster to use on the client side, because each regex is simply one lookup into a 3-column lookup table of old state, new state, and transition character. You can use the library here, which includes its own documentation to specify the needed compile files.

Reef

Reef in general is a great piece of research, and it's exciting to see more people think about zk regex approaches. While we were looking forwards to adopting advances such as Reef, upon closer examination Reef is unfortunately not useful in the DKIM setting.

The primary reason is that 'before Reef can be used, the document D needs to be committed with a polynomial commitment for multilinear polynomials that allows Reef’s NP checker to cheaply read arbitrary entries in D' (page 2). Unfortunately, the existing use of DKIM uses SHA256 of the commitment, so you cannot use their commitment scheme in practice for existing emails without incurring a large overhead to prove commitment equivalence.

A secondary reason is that it leverages recursion via using Nova directly, but other computations such as RSA are very inefficient or impossible within Nova without newer Nova innovations such as Cyclefold, which have overheads that in practice negate the benefit of using non-recursive circom. I am open to seeing future implementations improve this speed, but the current tooling is not faster for end-to-end email verification in ZK in practice. Skipping automata rely on Nova to skip all sections of form .+ but not [^a]+, but all our existing email regexes require the latter style of constraint i.e. in the format [^;]+; to reveal all characters upto the semicolon. It may be useful however, when a regex match occurs entirely in the middle of a regex i.e. there are characters after the semicolon in our above example -- again however, this relies on a Nova-style proof system which is hard to combine with the rest of zk email, especially with non-IVC friendly expensive wrong field math i.e. for RSA plus a 20M+ constraint recursive proof to post on-chain.

We have lookup-based regex code in Halo2 that performs much better than our Circom code, but was left out of their benchmarking -- however they are correct that many more improvements such as hybrid tables can be made to such lookup arguments -- because in practice regex matching with lookups is not a bottleneck, and efficient extraction becomes a larger bottleneck.